This article contains spoilers for "Succession" season 4.

Before he terrorized the planet as the CEO of Waystar RoyCo, "Succession" star Brian Cox played the world's most infamous cannibal: Hannibal Lecter, in Michael Mann's "Manhunter."

The final episode of HBO's "Succession" airs tonight, and fans are eager to see how the torrid tale of the warring Roy siblings ends. Jesse Armstrong's brutal satirical drama about the backstabbing machinations of a media mogul (who definitely isn't Rupert Murdoch) became an instant critical darling and has enthralled audiences from the start. It's a scathing portrayal of the weak-minded bullies and wannabe social climbers who populate the inner circle of a CEO's unimpeachable corporate powerhouse. At its heart is Logan Roy, the merciless businessman who will (and did on multiple occasions) throw anyone under the bus to retain his iron grip on Waystar RoyCo.

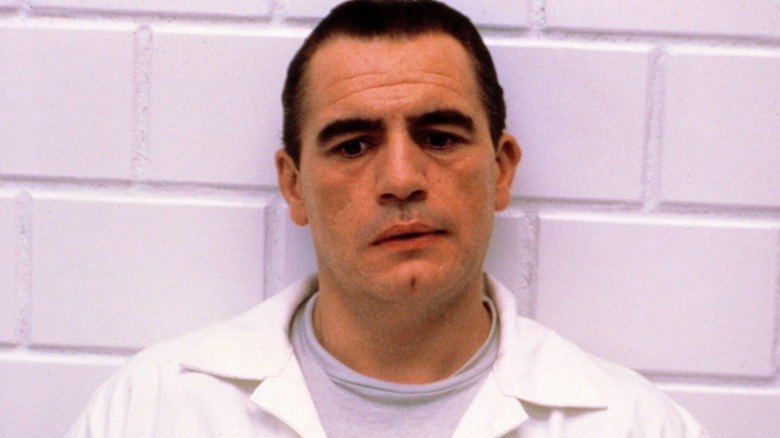

As played by Scottish character actor Brian Cox, Logan is a fascinating beast: a petty figure of intense force who views concepts such as a moral compass or love for his children as total wastes of time. While Roy died just three episodes into the fourth and final season, his ghost looms heavily over the episodes that follow, a reminder that nobody, least of all his four kids, can escape his bleak shadow.

Cox has had a long and varied career, working with everyone from Spike Lee and David Fincher to Adam Sandler and Scooby-Doo. He's a Shakespearean actor who has headlined musicals, played Winston Churchill, and chewed out Nicolas Cage's writing skills in "Adaptation." Logan Roy may be the character who defines his career for a certain generation, but at the beginning of his work in films, Cox played a very different kind of monster.

How Hannibal Lecter Came To Be

Thriller writer Thomas Harris penned "Red Dragon" in 1981: a crime novel about Will Graham, an FBI profiler brought out of retirement to work on the case of a serial killer nicknamed the Tooth Fairy. In order to catch him, Graham is forced to turn to Dr. Hannibal Lecter, an erudite psychiatrist and cannibal whom Graham caught — but not before obtaining serious physical injury. Unlike many crime novels of the era, "Red Dragon" put a major focus on the psychology not only of its villain but its wounded hero, a troubled genius haunted by crimes past and present. The novel was a big hit upon release, with Stephen King praising it as "probably the best popular novel to be published in America since 'The Godfather.'"

"Manhunter" would eventually spawn two sequels, a prequel, and a bunch of adaptations that put more focus on Hannibal Lecter than the actual heroes of the narrative. It's not hard to see why. He's a fascinating creation: a brilliant sociopath with no qualms about reducing his fellow man to meat. The tête-à-tête between Lecter and Graham makes for some of the most enthralling parts of the book series, and formed the backbone of the excellent NBC TV adaptation, "Hannibal." But long before that, before "Silence of the Lambs" and parody musicals and fava beans with chianti, there was "Manhunter."

How Michael Mann Adapted Red Dragon

For over 40 years, Michael Mann has been defined as a filmmaker of intense precision — a perfectionist who will happily re-edit his own films years after their releases to bring them closer to his vision. Indiewire described him as a director fascinated with "stories pitting criminals against those who seek to put them behind bars," adding: "His films frequently suggest that in fact, at the top of their respective games, crooks and cops are not so dissimilar as men: they each live and die by their own codes and they each recognize themselves in the other." Who better to adapt "Red Dragon" for the big screen? Mann is also a man of style, a proud adopter of digital filmmaking in its earliest days, and perhaps the most appealingly '80s director of that decade. "Manhunter" is a blend of his most distinct qualities, thematically and visually.

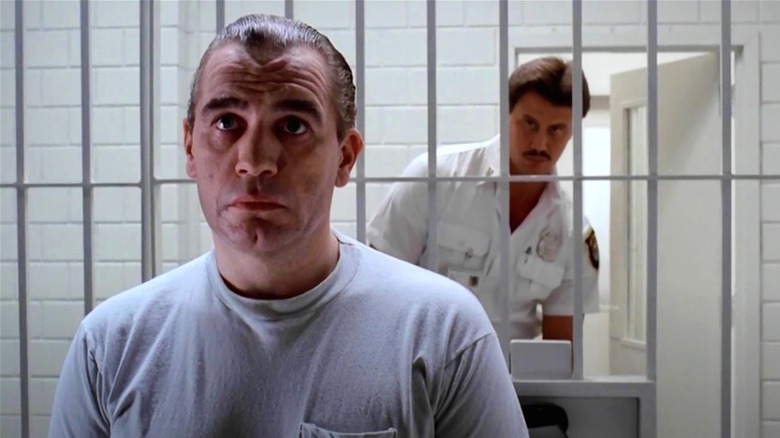

William Peterson, later better known for starring in "CSI," plays Will Graham, forced back to work with the FBI by the terror of the Tooth Fairy. He initially promises his wife he will go only to look at the evidence then come home, but it doesn't take him long to sink into the mental chaos of this killer, as well as the clutches of Dr. Hannibal Lecktor (he is renamed here for seemingly no reason). Later, we see the Tooth Fairy at work: a quiet yet foreboding man named Francis Dolarhyde who seeks acceptance from others and turns to Lecktor for a twisted kind of companionship.

While the adaptation of Harris's novel is pretty loose in places, Mann understands the allure of figures like Hannibal and Francis Dolarhyde with chilly precision. Contemporary critics dinged Mann for being too focused on his art-deco visuals and color cues, but those choices help to draw sharp parallels and contrasts between our broken hero and the monsters he shares a dangerous affinity with. What do you need to catch a killer? Someone who seems eerily close to becoming one himself. In the end, that promise is fulfilled.

Brian Cox's Hannibal Isn't The Fun Kind Of Monster

We all have an idea in our head of what Hannibal Lecter is like, and for most of us it's the image defined by Anthony Hopkins' Oscar-winning performance in Jonathan Demme's "The Silence of the Lambs." Lecter is scholarly, a social animal who enjoys manipulating those he deems beneath him (which is literally every human being). As played by Hopkins, he's a theatrical figure — someone who hasn't had a captive audience for a long time before the naïve but plucky Clarice Starling turns up outside his cell asking for his help. As oft-mocked as the performance has been, it holds up as a portrait of a new kind of serial killer: one of aesthetic concerns and intellectual superiority.

In the book "Hannibal," which Ridley Scott loosely adapted for film because it's truly bananas, Lecter is almost otherworldly in terms of his psychological power. This is something that Bryan Fuller's TV re-imagining would grasp onto, with Mads Mikkelsen admitting he wanted to play the character as though he was literally Satan.

By contrast, Brian Cox's Hannibal is a much colder figure. He's not debonair, he doesn't openly relish toying with Will Graham or lean into the mythic nature of his own status as "Hannibal the Cannibal." He's not Satan. He's human, unnervingly so. There's nothing remotely likeable about him, which stands in sharp contrast to the charisma of Hopkins and Mikkelsen, who lean into Hannibal's seductive nature. This Lecktor is rude (which would make him perfect fodder for Mikkelsen's table). He does not seek to be entertained. When he's reunited with Graham while behind bars, he seems bored by his presence. By the time he begins antagonizing him, you want him dead, and quick. The fun of Hannibal lies in watching him run rings around everyone else, even though he's undeniably the villain of every scene. Cox, however, is cruel in a way that is often tough to watch, as mightily effective as it is.

As stylish and inimitably Mann-esque as the rest of "Manhunter" is, the Hannibal scenes are stark and almost mundane in their reality. Nothing there would look out of place in a true-crime documentary or a David Fincher movie. The Tooth Fairy revels in putting on a show; Hannibal Lecktor is over it. Just when you think he seems sort-of normal, he reminds you that he is still the most dangerous person in the entire film, and he doesn't have to try that hard.

There's always something familiar about Cox's villains, whether it's Logan Roy, Hannibal the Cannibal, or someone like Colonel William Stryker, the anti-mutant scientist in "X-Men 2." They're men rotted by power yet simultaneously made immortal by it. He rejects the urge to romanticize, instead favoring the familiarity of the monsters we encounter every single day. To put it bluntly, he's scary as hell. No wonder the Roy kids can't wriggle free of his grip from beyond the grave.

Read this next: Horror Movies That Make Us Root For The Villain

The post Long Before Succession, Brian Cox Played a Different Kind of Monster in Manhunter appeared first on /Film.