Everybody makes mistakes. It's a fact of life. People live, learn, and grow because of the mistakes they've made or seen others make. But when the ones making mistakes are celebrities, public figures, and pop culture icons, fans will label them as "problematic faves" by recommending their work or singing their praises with a caveat attached.

An adept producer of problematic faves is Walt Disney Studios. Independent of its famous namesake, who has his own laundry list of problematic behaviors — such as union busting and getting his employees blacklisted by testifying in the McCarthy trials — the renowned studio that became famous for its exemplary work in animation has had their fair share of questionable moments throughout their nearly 100 year history.

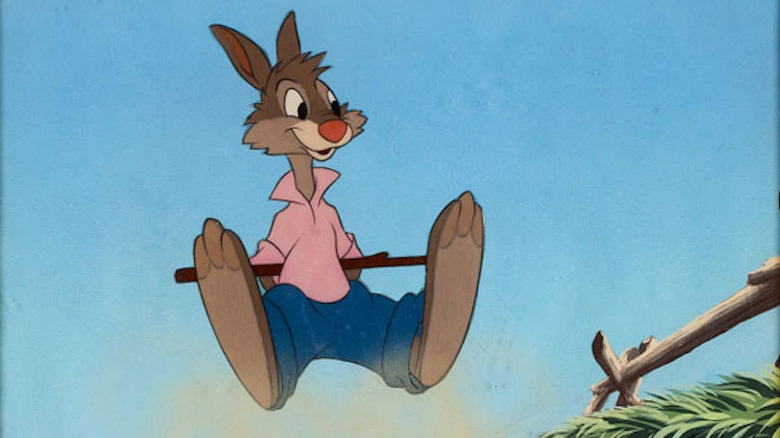

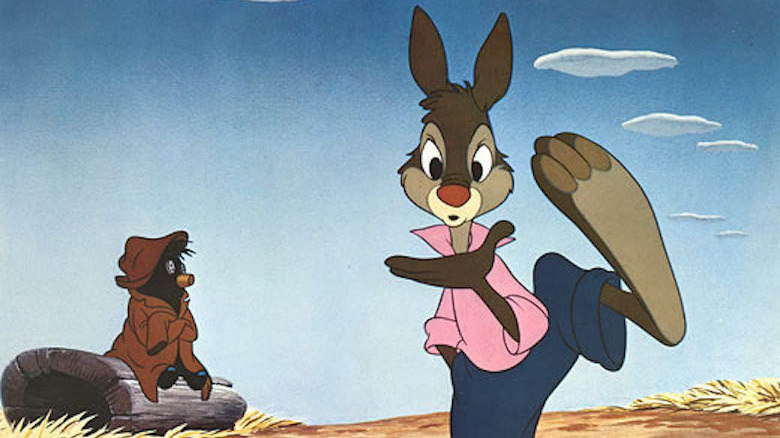

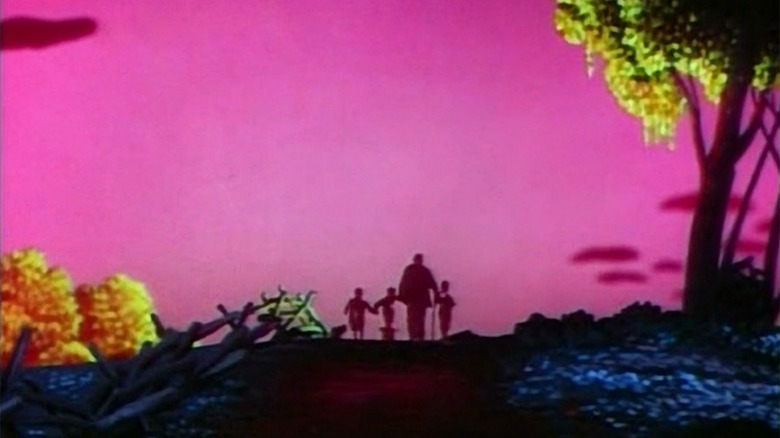

The most noteworthy example is the 1946 live-action/animated musical hybrid film "Song of the South." This adaptation of Joel Chandler Harris' Uncle Remus stories blazed a trail for animated classics like "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" and recent Disney+ release "Chip 'N Dale: Rescue Rangers." It also earned an Academy Award for the catchy tune "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" and inspired the fan-favorite Disney Park attraction Splash Mountain. Plus, it allowed star James Baskett to become the first Black man to earn an Oscar. However, its story was also deeply racist, presenting a false, romanticized version of plantation life in a post-Civil War South.

Despite this, and on top of the fact that "Song of the South" has yet to escape the Disney Vault for an official US home video or streaming release, the company rereleased the film theatrically four times and incorporated the more digestible elements of the story into many facets of their brand. But all that's just the tip of the iceberg, since this project was stewing in controversy even before pre-production began.

The Folklore Of The Old Plantation

Before getting to the many controversies of Disney's film, let's first look at the source material. "Song of the South" is based on the "Uncle Remus" stories written by Joel Chandler Harris. Although, "written" is a term used very loosely here. Harris was a white pro-Confederacy journalist from Georgia who spent a good portion of his formative years during the Civil War on a plantation. When he wasn't performing his duties as an apprentice at Joseph Addison Turner's newspaper The Countryman, Harris spent his time at the slave quarters of his employer's Turnwold Plantation, listening to traditional African folktales from people like Uncle George Terrell, Old Harbert, and Aunt Crissy, who would all become the foundations of the Uncle Remus character.

Around fifteen years later, Harris began compiling the stories he heard from slaves about characters like Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox, and Br'er Bear into his first book, titled "Uncle Remus: His Songs and Sayings." According to R. Bruce Bickely Jr.'s book about the author, Harris wanted to "preserve in permanent shape those curious mementoes of a period that will no doubt be sadly misrepresented by historians of the future." He also utilized a "Black dialect" to "retain authenticity" in his parables.

However, it doesn't sound like Harris merely wanted to preserve the culture of the people who originated these stories. Rather than crafting original tales of his own, he capitalized on the folklore of slaves by transcribing their stories and taking credit for them. Despite being praised at the time and inspiring contemporary writers like Mark Twain, the legacy of Harris' major works have come to be seen as the definition of cultural appropriation.

Into The Briar Patch

After hearing the Uncle Remus stories as a child, Walt Disney was also inspired by Harris' work and wanted to adapt it them a film. Once talks began with the Harris estate in 1939, Disney was given the green light to start production on "Song of the South" in 1944. That's when Southern-born screenwriter Dalton S. Reymond joined the project to work on the script. That's also when the first of many red flags went up.

When Raymond's 51-page outline was submitted to the Hays Office, the censorship body declared that certain words and phrases such as "massa" and "old darkey" be removed from the treatment. The studio then brought in writer and performer Clarence Muse, the first African-American actor to appear in a starring role thanks to 1929's "Hearts in Dixie," to consult on the script. However, this consultation didn't last long because Reymond refused to rework the Black characters into anything other than Southern stereotypes. When Muse left the project, he reached out to various Black publications to criticize Reymond's work. Many claimed that he was just mad that he didn't get the part of Uncle Remus in the film, which ultimately went to James Baskett. But when the NAACP and the American Council on Race Relations requested access to the treatment in an effort to give feedback, they were denied.

The script was ultimately credited to six white men: Morton Grant, Dalton S. Reymond, Bill Peet, George Stallings, Ralph Wright, and surprisingly, the known communist Maurice Rapf. Disney conceded to Rapf, "I know that you don't think I should make the movie. You're against Uncle Tomism, and you're a radical," but hoped to pre-empt criticism by getting his divergent voice on board.

Gone With The Birth Of A Nation

As "You Must Remember This" host Karina Longworth explored in her incredibly well-researched podcast series about "Song of the South," it seemed like Disney was chasing the award-winning formula that yielded results for "Gone With The Wind" and "The Birth of a Nation": Revisionist racism + groundbreaking filmmaking = massive profits. Though he nailed down the nostalgia for the false plantation myth and the technological innovation, the script left a lot to be desired. In his 1946 review in The New York Times, Bosley Crowther wrote, "the ratio of [live-action] to cartoon action is approximately 2:1 — and that is approximately the ratio of its mediocrity to charm."

Despite a plot that left the audience divided artistically and politically, the movie still earned accolades for its music. The score was nominated in the "Scoring of a Musical Picture" category and won "Best Original Song" at the 20th Academy Awards for "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah." The music and lyrics were credited to Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, but there is a bit of controversy surrounding this song's origins.

Disney historian Jim Corks alleges that the phrase "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" is "an expression of happiness and joy, reportedly invented by Walt Disney himself who had a fondness for these types of nonsense words from Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo to Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious." But as Longworth explores on her podcast, the song is likely influenced by the pre-Civil War song "Zip Coon," a variation of "Turkey in the Straw" that inspired the blackface minstrel show character of the same name that was used to make a mockery of free Black people. Yet even with its racist origins, the song was the last enduring element from the film that the studio continued to insert everywhere, from sing-along video tapes to theme park attractions. At least, until recently.

The Laughing Place

The final controversy associated with "Song of the South" that we'll be looking at is the monument erected in its honor at the Disney theme parks in California, Florida, and Tokyo. Dubbed Splash Mountain, guests can join the adventures of Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox, Br'er Bear, and all their animal friends on a log flume dark ride that goes through several of Uncle Remus' stories, set to "How Do You Do?," "Ev'rybody Has a Laughing Place," and "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah," which were all featured in the movie.

Splash Mountain was conceived in 1983 by legendary Imagineer Tony Baxter in an effort to get more foot traffic through Bear Country in Disneyland. Originally called the Zip-a-Dee River Run, former CEO Michael Eisner suggested Splash Mountain as the name in order to help promote the 1984 Tom Hanks film "Splash." After being delayed and going way over budget, the attraction finally opened in Disneyland in 1989, then in Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom and Tokyo Disneyland in 1992.

Due to the its association with "Song of the South," which had just been re-released theatrically in 1986 for its 40th anniversary shortly before the ride opened, there has always been some degree of criticism from Disney Parks fans. 30+ years later, the Mouse House finally decided to listen to those concerns when in 2020, the company announced that Splash Mountain would be re-themed into an attraction based on "The Princess and the Frog." The plan is to unveil the updated version called Tiana's Bayou Adventure on both U.S. coasts in late 2024. As for Tokyo Disneyland, no official word has been given about re-theming, but The Oriental Land Company (who operates the theme park) is apparently in talks to follow the American parks' lead.

Sooner Or Later

As you can see, the Walt Disney Company has a very complicated history with "Song of the South." From the moment the project was announced, it rubbed some people the wrong way. Then, when audiences laid eyes on the skewed view of plantation life in reconstruction-era America and heard former slaves singing lyrics like "When you're old and grey, you better be thankful that he let you stay," many of them knew, and many more in future audiences knew that their reservations were totally justified. But like the problematic faves that Disney are, it took them a little while to come around to the fact that this movie didn't need to exist and should not continue to be promoted and profited from.

Since there are no plans for a physical or digital release any time soon, and Splash Mountain is going the way of the dodo, time will tell if the company also phases out "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" from their musical rotations. Until that happens, with the film and its characters more out of sight than ever, let's just hope that "Song of the South" remains locked away in the Disney Vault and stays in the past where it belongs.

Read this next: Ranking All Eight Muppet Movies On The First Film's 40th Anniversary

The post The Song of the South Controversies Explained appeared first on /Film.